HEAL Volume 2

HEAL seeks to celebrate the human experience that is medicine. It longs to prevent preoccupation with the difficult aspects of medicine and focus on the beautiful and meaningful work that medicine can be. This volume is scheduled for publication in the fall semester of 2010. We have already secured funding for this project and are very grateful for the leadership at Florida State University College of Medicine, whose vision and faith have made this work possible. It is very exciting to see how this work has taken off, and we hope that it can continue to serve as an inspiration for all those who are involved in medicine--patients, staff, and providers.

HEAL seeks to celebrate the human experience that is medicine. It longs to prevent preoccupation with the difficult aspects of medicine and focus on the beautiful and meaningful work that medicine can be. This volume is scheduled for publication in the fall semester of 2010. We have already secured funding for this project and are very grateful for the leadership at Florida State University College of Medicine, whose vision and faith have made this work possible. It is very exciting to see how this work has taken off, and we hope that it can continue to serve as an inspiration for all those who are involved in medicine--patients, staff, and providers.

- Abuela Nilda by José E Rodríguez M.D.

- Night Memories by Carol Warren

- Love by Carol Warren

- Alliteration by Carol Warren

- Understanding by Eric Heppner

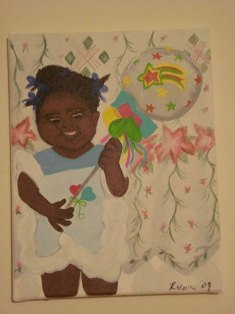

Abuela Nilda by José E Rodríguez M.D.

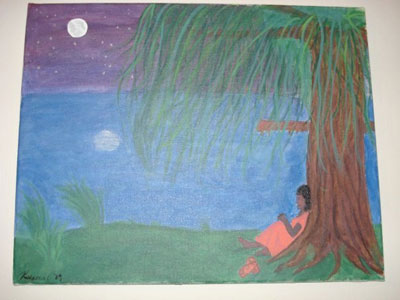

Night Memories by Carol Warren

Wile away the hours

Wile away the hours

Spending time like rain.

Colliding pictures rushing

Will not come again.

Until you look at nothing

And see a painted sky.

Purple of the shadows

Once again will die.

Crouched upon life’s doorstep

You find it closed tonight.

Do not look for comfort

With the dying of the light.

Sunset opens windows

Night comes creeping in.

Never curse the darkness

Wear it like a skin.

Let the memories clamor

Let them rip and tear.

They can not pierce the armor

Black armor that you wear.

Love by Carol Warren

Alliteration by Carol Warren

Understanding by Eric Heppner

Sweet Sophia, Wisdom's daughter,

sometimes stays with me.

And I can stand, a man complete,

in her pleasant company.

Yet, she is as capricious

as the water in the sea

And wont to let me wander

In Lethe's agony.

- Persona By Evelin Ramirez

- Vision by Samuel Williams

- Mi Orgullo by Jose Oyola

- Rosa Parks by Samuel Williams

- A Reverend, a Doctor and a King! by Samuel Williams

Persona By Evelin Ramirez

This is a poem that uses Myth, Allegory, Archetypes and other tropes to reveal the behavioral façades that concealing dysfunction. The Poem alludes to the poet’s childhood, ethnicity and child abuse. Using image-driven and senses-heightening descriptions, the vignettes aim to transport the reader through a reverse chronology of experiences which ultimately lead to the Poets self-discovery and healing.

This is a poem that uses Myth, Allegory, Archetypes and other tropes to reveal the behavioral façades that concealing dysfunction. The Poem alludes to the poet’s childhood, ethnicity and child abuse. Using image-driven and senses-heightening descriptions, the vignettes aim to transport the reader through a reverse chronology of experiences which ultimately lead to the Poets self-discovery and healing.

One is a goddess

a Botero woman,

a real life Willendorf

that smells sweet,

exotic as Neroli oils,

Egyptian rose,

like a palm of cloves

so sweet

you could bite into

her flesh and she’d

taste like tres leches;

milk cake. The sophisticated

one that seduces men with

charm, salsa and sonnets.

Charms her Pashminas

like snakes coiled

on that body, veiled

by some of those scarves

in cut velvet plums

crimson wraps, silk

tattooed with

painted feathers.

Carismática. Big as

her smile, she is soooo beautiful…

Another is a sex-

Goddess, the porn-star,

glossy-pouted, flowing

mane, perfectly manicured,

doesn’t eat, moans on cue

does the triple double twice

in a row, the pearly eye

butterfly, makes you fly

she is ascending

like a dragon.

Measures her waist,

glares in the mirror

like The Fragrant

Concubina. Powder

rice-pearl-jade on her tear

-striped face.

The succubus. Australian Wild

Cat that purrs but doesn’t sleep.

Can’t remember her lovers’

names, her fingers are sooo thin…

Then there’s the addict, a

wine connoisseur, the broken one

that loves the Blues, devotee of

Alberta Hunter and Nina Simone.

Hums Wild as the Wind

Writes and dreams

of humpback mermaids,

she plays the piano

she can sing, she scats and rat,

tat, tats with friends but she’s

fuckin with you; she Can Sing!

Make you cry too.

She’s the vessel

the pure one.

Pure persona. The love-warrior

who suffers. Can you

hear her weeping

right now?

She weeps like a Devadasi.

She weeps like a coffin-birth-child.

Weeping for L'amour

Mi amor

languish. She is a seductive

persona, she’ll have you

join in to regale

your Greek tragedy stories, makes

you cry, she’s weeping,

weeping, weeping,

like a Black Weeping

willow, her hair is sooo long…

What about the comedian?

She’s a hoot! Does funny voices

‘cause humor transcends

geography, genealogy, she

is funnier than her racist dead

grandmother who called her

a spear-chucker and longa de mierda.

She’s not sarcastic, just brilliantly

funny, has made several people piss

their pants (4 times)

She laughs like an epic novel.

Laughs like new jazz, like

Jazz Timbal staccato, laughs

like a bleeding heart baboon

A pandemic laugh that echoes,

and quivers in cavernous hearts.

She can make the whole place

laugh, she is sooo cool…

What about the Diva?

Shit! The black Puma? Coño!

The walk. She is articulate

sexy, dresses like the runways

she is the real Decoy, well-

versed in Psalms and Sanskrit

poems, briefly studied the Koran

not a quasi-intellectual.

Her appetites are controlled.

Even in her rituals

of thrill, she is peaceful

even-breathed as she lulls

her men within, doesn’t share

the fiscal miseries, spends

her insufficient funds.

She’s paying. Her treat!

She’s got it together, skips

mortgage payments, hustles

the IRS sometimes, let’s not

talk about the coke

billowing like blackboard

chalk at 17, just know she’s a

fucking Trukah! Keep on

truckin baby! Diva

sashaying, she is sooo pretty…

Then there is the kid

hiding a patch of hair

bleached with hydrogen peroxide

poured on her head to clean

wounds inflicted by Mom. A

pillowy-mouthed girl who

can affect any accent, looks 21

at 11-years-old, knows sophisticated

dialects of men’s desires.

Languages ciphered with

liquored words.

The girl that wets the bed.

Dances with death disguised

as her great-aunt’s heart pills.

She plays the piano too

but her voice is faint, smaller

than a marbled moth.

She really is a little kid,

covers the other personas

with 1,000 thread count Turkish

linens. Dims the lights.

She is the Protector. A halved-one.

Curious-terrified-scarred

and resilient. She gentles

feral cats, lavishing

kisses, she is sooo little…

She has love to heal herself

and has poetry to forgive her mother.

Vision by Samuel Williams

I had on my new clothes

I had on my new clothes

Even new shoes on my feet.

I was there for church and bible study

I went to the back and took my seat

Yes I am doing good now

Doing things on my own

Soon I’ll be publishing poems

And God will bless me with a wife and a home

I talked to some of my friends

We were all having some fun.

I said something that I shouldn’t have said

Did something I shouldn’t have done

I knew I was different

I felt God touch my heart

I knew I should set a standard

But then I knew I would be set apart

Walking to my car one day

I was not looking straight

I heard the car tires screeching

But now it’s too late.

I’m standing in this room

And I can see the heavenly gate

O no I forgot to pray

I thought I had time to set it straight.

An angel walked up to me

He had a book in his hand

I knew it was the book of life

Now I wonder, “Was I part of the plan?”

I told him my name

And he began to look

Then he looked at me sadly and said

“Your name is not in this book.”“

Angel, this is a dream

No, I can’t be dead!”

He closed the book and turned away

He whispered, “You cannot proceed ahead.”

“No, this can’t be real, Angel.

You can’t turn me away

Let me talk to God

Maybe he’ll let me stay”

He led me to the gate

Jesus came up to me

He did not let me in but said,

“Your whole life I see.”

“Jesus” I cried, “Please!

Don’t cast me away from you!

Tears ran down his face as he said

“You knew what you needed to do.”

“Lord, I went to church with many

Hypocrites that were not being true.”

He took a step back and asked,

“What does that have to do with you?”

“Lord, my family claimed to be saved

They weren’t being real, you know?”

He said, “I died for you,

Now I have to go.

”I fell to my knees crying to him

“Lord I plan to be real tomorrow.”

I couldn’t make him understand.

I had never felt such sorrow.

Then it hit me hard I said,

“Lord, where will I go?”

He looked into my eyes and said,

“My child, you already know.”

“Please, Jesus” I begged.

“The place is so hot!”

It seemed to trouble and grieve him

He whispered, “Depart from me, I know you not.”

“Lord you’re supposed to be love.

How can you send me to damnation?”

He replied, “With your mouth you said you loved me,

But each day you rejected my salvation.

”With that, in an instant

Day turned into night.

I never knew such torture could be

Now too late, I know the bible is right.

If I can tell you all anything,

Hell has no age.

It is a place of torture

Separated from God and full of rage.

You know I thought it was funny

But this one thing is true.

If you are not a member of the Church of Christ

Guess what? Hell is waiting for you.

Mi Orgullo by Jose Oyola

When I first began practice, I was trying to help a young patient who had rheumatoid arthritis. He desperately wanted to get better, and he was trying hard to keep his talents. He gave me this painting, and it still hangs in my office. On the back it says, “For Dr Rodríguez, a great Boricua.” I hope I can live up to his challenge.

Rosa Parks by Samuel Williams

The year was December 1st 1955

The year was December 1st 1955

And the south was divided by segregation

The civil rights movement was very much alive

And it was in need of some vigorous stimulation

The momentous event occurred in Montgomery Alabama

And no one could imagine its true magnitude

Of one little lady who was caught up in a system

That was both wicked and rude

Rosa parks was as tired as tired can be

She was hurting from her head to her feet

Yet she would change our nation’s history

For refusing to give up her bus seat

For refusing she was put in a cell

Fingerprinted and put in jail

Still those who gathered to pay her bail

Knew she had rung the right alarm bell

Rosa parks didn’t want confrontation

All she wanted was some old fashioned respect

But when she got the nations attention

She stood firm and stuck out her neck

The civil rights movement would last much longer

But Rosa’s stance helped broaden the fight

Thanks to one little tired lady

Who sat down because she knew she was right.

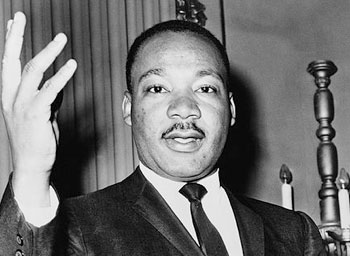

A Reverend, a Doctor and a King! by Samuel Williams

As I find raging insults behind your death

I find joy at what you left behind

A story of love, unity, freedom and peace

We spent hundreds of years trying to find

A true beloved leader you were

Who lived on freedom songs in your heart?

And heavenly arms awaited you

For a war you tried to end but did not start

You too are free at last, because your spirit still lives

And too much hatred and racism still exists

But through your words of wisdom

We now fight without guns, knives or our fists

We now truly understand your fight

Because Satan’s ignorance no longer blinds our gleam

But what we represent now and pass along

Is peaceful knowledge and of course your dream

Farewell freedom soldier

Job well done and thanks for the tomorrows you help bring

But what could we expect from

A reverend, a doctor, and a King.

des to the poet’s childhood, ethnicity and child abuse. Using image-driven and senses-heightening descriptions, the vignettes aim to transport the reader through a reverse chronology of experiences which ultimately lead to the Poets self-discovery and healing.

- Two PE Insomnia by Eva Bellon

- The Battle of Perspectives

- The Gown by Jill Ward

- Stitches by Stephanie Pollock

Two PE Insomnia by Eva Bellon

How silly to be scared to fall asleep. Yet here I sit again- completely exhausted but awake. There is something so strange about almost dying: your body stops feeling like it belongs to you. It defies you and no longer listens to your demands.

How silly to be scared to fall asleep. Yet here I sit again- completely exhausted but awake. There is something so strange about almost dying: your body stops feeling like it belongs to you. It defies you and no longer listens to your demands.

For instance, take the simple act of breathing. We do it so carelessly. You all take it for granted, I know I did. When your body revolts from breathing, because it hurts too much to take in even the slightest bit of air, it changes you. I now have an irrational fear of not breathing. Well, I suppose it is not irrational. Most days I still wake up and it feels like someone is sitting on my chest. You know how hard it is to concentrate on things with someone sitting on your chest? I have a memory of that first night in the ICU and the nurse calmly waking me up (he was an angel by the way) telling me it was important to put the oxygen on me now. If he wasn't so calm I would have gone into complete panic. I knew that the pain and strain on my lungs was so extreme that my body no longer wanted to breathe. I had to consciously decide to let air in. Thus began my fear of not breathing in my sleep.

I can't even begin to describe the fear and calm of death. Yes calm. Panic and calm meet at a place called death. Or maybe it was just unconsciousness. I almost landed there once. The calm scared me more than any emotion I could ever express. For a split second amongst all my horrible pain, I was calm about not breathing. It hurt less and that is all that I wanted in the world. They teach us to ask patients on a scale of 0-10, 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain you could imagine, where does your pain rank? What rank do you give when you can no longer comprehend what the numbers mean? What number do you give when it is worse than anything you could ever imagine and all you wish for is something that will end it? All you want to do is slip into unconsciousness to escape, but then you don't and they ask you for a number because you are conscious. It was a 12, no a 20. There isn't a number that can express that feeling.

Everyone is worried about me catching up in medical school. Don't get me wrong I know it is important and I want more than anything to catch up, to feel normal again. It is hard to force emotions about class. The normal me would be losing it by now to be this far behind on the Monday of exam week. I am so emotionally spent that I don't have the energy left to be anxious about something like a block exam. Here is what I know: How about endocrine physiology, how about Cortisol? Yeah, I get cortisol- my body is under so much stress that my high cortisol levels have begun to affect my hippocampus. How do I know? Because I can watch a lecture three times and feel like I have never heard it.

So when I am asked how I'm doing, how do I respond? I can breathe without reminding myself to now. I can actually rank my pain 0-10 (it is about a 3 right now). I have grown to despise the clots left in my lungs. They are part of my life for at least another month or two. And after that? Scar tissue? Who knows? All I pray is that my heart goes back to normal like they say it will. All I pray is that this Coumadin, that I have grown to love and hate all at the same time, does its job. Thin my blood to save my life and all the while making me freeze, get exhausted, feel like I'm going to faint from time to time, and bleed at the drop of a hat. It will be my bittersweet knight on a white horse for at least another 6 months.

But, I am alive.

Now THAT is something that everyone takes for granted far too much.

I am alive.

God has a plan for me and if you say it’s not so- look at my CT. You know how many people have told me I am lucky to be alive? Thirty percent of people die during the first hour of a pulmonary embolism. I had two and walked around with them for two and half days. The doctor that took the Echo of my heart and looked at my chart said "how are you not on a ventilator and unconscious?"

So I let him know, “Because somebody up there is looking out for me”.

So ask me again how I am doing, how am I holding up?

I am alive.

The Battle of Perspectives

It is amazing how one situation can look entirely dissimilar when given differing perspectives. As far as serving in an underserved population where the patients have no insurance and they desire free or small expenses for treatment, the outlooks are usually opposed between the doctors and the patients. This paper will be based on my brief encounter with a free hospital in Jamaica, a 3rd world country, and how the view of the doctors versus that of the patient can certainly elicit the ‘outside audience’s’ understanding when given both scenarios.

It is amazing how one situation can look entirely dissimilar when given differing perspectives. As far as serving in an underserved population where the patients have no insurance and they desire free or small expenses for treatment, the outlooks are usually opposed between the doctors and the patients. This paper will be based on my brief encounter with a free hospital in Jamaica, a 3rd world country, and how the view of the doctors versus that of the patient can certainly elicit the ‘outside audience’s’ understanding when given both scenarios.

As a patient coming to the hospital for the first time, you are hit with the reality that you are among the hundreds of ill people without medical insurance in the country. This is initially brought to your attention by the extremely long line that you have to join. A line so long that it curves out to the street corner, but despite your serious aches and pains this process cannot be deterred. You see the faces of the people in the lines and some appear much worse than you, while others seem to have lost their way. You see the helplessness, the desire for a better means of obtaining the medical attention needed, but acknowledge the monetary hindrances that prevent fulfillment of these dreams. You feel the sun pelt down on your skin as you wait and wait and wait only to be given a thick amount of paperwork to fill out before someone is able to see you. You are shouted at if you try to ask a question for clarification, and the other patients are so caught up in their own demise that it seems as though it is you against the ‘system’ of the entire hospital. However, as you have filled out the forms and are then taken in for interview, the gravity of your situation is realized and you are immediately admitted and a number of tests are ordered. Finally, you feel as though some progress is being made and you patiently await the results.

A few days go by and you can barely speak with the nurses who fly by your bedside in a hurry to something more pending in another place. There always seems to be something more pending in another place. As your health deteriorates and your strength likewise diminishes, you become conscious of the fact that if you get to see the doctor twice a week, that it is a great gain. The nurses might stop by if they notice that you have been lying in your own urine for a few hours and the smell has become distinct. No time, no time to visit and talk to the patients. No time to stop and encourage the patient. No time to explain in detail the prognosis and the plan of action to be taken. You realize that people around you are dying or just giving up and going home and even though you would rather be in the comfort of your own house you really want to know what is happening with your body. As your shouting for help decreases, and your ability to eat and breathe on your own ceases, you wish you were financially able to obtain a better plan of care. However, the best medical treatment is not a ‘right’ in this hospital, it is a waning desire. Soon, you have accepted the fact that there is nothing more you that you can do. Time cannot heal in this situation and loneliness certainly does not help and so as you take your last few breaths, you reflect on your life before this and you hope and you pray that somewhere out there you were able to make a positive impact and give all your attention to someone who desperately needed it.

From a physician’s perspective, you wonder how you will ever be able to attend to all these people and give them the best care you were trained to give. How can you possibly empathize with each person’s story and still find the time to explain in detail the course of their illness and the plan of care. You are among the few doctors working here and you realize each day as you are given your patient load that it will be impossible to see them all, reach them all, and still maintain a level of sanity that is needed to continue throughout the day. As you walk around you see helpless faces and deteriorated bodies lying motionless awaiting your help and healing. Voices call out to you from all of the rooms, each seeming to need your help more than the others. Which do you answer? You develop a schedule and make your daily rounds, trying to see as many patients as you can, and for as brief periods as possible so that you can squeeze the board meetings, the family calls, the paperwork, the assessment of lab results, and the time to breathe into a single day. Of course you realize that some patients will not get the attention and care that they so rightly deserve and long for.

You realize that this one patient whose body was a lot stronger and whose voice was a lot louder a few weeks ago has not been heard in a while. You go over to her bedside and you see her life quickly passing by and still there is no diagnosis. You order a few more tests to be done so that she can be helped, but the lab is overwhelmed and the dates given for testing are much later than you think she can hold out. You speed up the process and even though the tests are done earlier due to your influence, the results are nothing definitive and so another approach has to be taken. You think, ‘whenever I get a chance, possibly next week, I will try again and see what can be done for her, while, of course attending to the other fifty patients that are also calling my name’. However, you never get back to her in time, as she could not hold out any longer. She lay there with a different form than when you first saw her, a face that is emaciated, a smile that has faded, and a breath that has been taken away. As you start to reflect on what could have been done differently, your attention is quickly commanded by a nurse shouting that a patient has gone into cardiac arrest and you are needed. One more day…one more life that you were not able to save, but still you must go on and do all that you can do to save the rest.

The Gown by Jill Ward

The Gown: A Pathography

I walked in wearing my white coat to make a point, and because I had just rushed from my medical school rotation to my doctor’s appointment. “Take everything off, including your underwear, and just put the gown on open to the front.” I had already drowned out the voice of the nurse. I know how to put on the gown, I thought to myself, I’m 27 years old and have had enough exams to know the routine of what to do and where to stand. The nurse knew this, didn’t she? Doesn’t she know who I am? She not only has seen me here three times in the last two months but she saw me walk in with my white coat on. The white coat, which clearly indicated my status in the medical community. I’m the one who says “Take everything off…” I still smiled and waited for her to exit. You have to act graceful at these visits, don’t you? Say “Good Morning” with a high-pitched squeak at the end to show your enthusiasm and how much you enjoy letting everyone see you half naked. I took off my white coat, hung it neatly on the chair next to the exam table, and then quickly took off the rest of my clothing.

I walked in wearing my white coat to make a point, and because I had just rushed from my medical school rotation to my doctor’s appointment. “Take everything off, including your underwear, and just put the gown on open to the front.” I had already drowned out the voice of the nurse. I know how to put on the gown, I thought to myself, I’m 27 years old and have had enough exams to know the routine of what to do and where to stand. The nurse knew this, didn’t she? Doesn’t she know who I am? She not only has seen me here three times in the last two months but she saw me walk in with my white coat on. The white coat, which clearly indicated my status in the medical community. I’m the one who says “Take everything off…” I still smiled and waited for her to exit. You have to act graceful at these visits, don’t you? Say “Good Morning” with a high-pitched squeak at the end to show your enthusiasm and how much you enjoy letting everyone see you half naked. I took off my white coat, hung it neatly on the chair next to the exam table, and then quickly took off the rest of my clothing.

Sitting on the cold exam table in what I would barely call a gown. It is paper after all… thin, see-through, humbling paper. Why even call it a Gown? Gowns are full, covering, and beautiful, made for parties, dances, and fun. “Isn’t that ironic?” I thought. Even more ironic was me, the fully capable senior medical student having to sit here waiting for the doctor to see me. Just this morning all the patients scurrying in the halls and in the waiting rooms were waiting for me. Now, I had been waiting for hours, to think I already sat in the waiting room for an hour and a half then after being triaged into a room, stripped down and donned with my Gown, I am made to sit in a freezing exam room and wait. I wanted to open the door and yell: “Hello, doctor, do you know who I am in here? My disease is not some routine visit, the others can wait. I need to be seen now!” But I was shivering enough now that my seat was becoming a little warmer and in all my voiceless frustrated efforts to summon the doctor from my ballroom exam room, I refused to give up that heat by moving. And more dreadful was the thought that getting up would risk my Gown falling off, or even worse… tearing. The only help I had was a thin plastic belt that tied around my waist to keep the Gown on me. Right, I thought as I looked down at the Gown, like that belt would save my breasts from falling out, or the bottom of the Gown from flinging up and exposing my buttocks.

My ballroom hardly had enough space to move, just about 2 feet to the door and 3 feet to the sides of the bed. I stared at the walls, decorated in pertinent patient-centered informational posters. My Ballroom, full of the things I told patients everyday in ‘layperson’ terms about their disease or condition. “Breast Development, Fibrocystic Breast Disease, Finding a Breast Mass”, my eyes danced over the poster titles in boredom.

The door finally opened, and then he knocked. What was that? He had already granted full view for every passing person in the hall and had made full eye contact before he even knocked. I quickly shuffled my Gown around, grasping and crinkling the paper to cover my bottom. I could feel the breeze of the opening and closing of the door and my tummy now showed, but perhaps I had to live with that for another shift of the Gown and it could be on the floor. I focused, I needed to gain my composure so I could intellectually get some work done here, and so I just crossed my arms as tightly over my breasts as I could and smiled. Rambling on and on, shifting through my chart, clearly he was busy today. “So we’ll need to biopsy, set it up on the way out, then be back in two weeks for follow up. We can talk about BRCA analysis then too.” His voice echoed loudly as if he were at the top of one of those long staircases you see in movies giving a speech. I sat there, shifting in dance as I felt my Gown falling or moving. My aunt must have had to go through something like this, the in’s and out’s of being diagnosed with Breast Cancer, a double mastectomy, a repeat surgery, and reconstruction. I had questions, concerns, worries, but he already had the door cracked open to leave before I could even recheck how much of me the Gown was exposing. I clung to my Gown for modesty, hoping not to be seen and the nurse scurried out with him to the next patient.

He didn’t even examine me. Did my Gown mean nothing to him? This dress should have signaled the need to do something to me, poking or prodding. I did not do this in vain! I quickly glanced over to my clothes, the mundane everyday clothing. I saw my white coat, hanging on the edge of the chair. Didn’t I know that what he said is what I would have said? Didn’t I know what a busy schedule he had, overbooked patients, and how unconcerned I should be?

I stood up and tried to rip off my Gown to hurry and get dressed. The paper flew in the air landing everywhere in the room. Being in a room that was not locked was worrisome for intruders so I thrashed harder to get out of the Gown; the paper had never seemed so strong and yet too thin to cover me. I had to fight it off my left arm and rip the belt off my waste.

It was over. I placed my Gown on the table, now all torn and disfigured. In all it’s gloriousness it could not grant me my one wish and desire. I put on my white coat. I grabbed my chart and went to check out. Opening the door I peered down the hall, catching glimpse of a woman clinging to her Gown as the doctor flung open her door.

Stitches by Stephanie Pollock

When I was 5 years old my mother developed late-onset schizophrenia. It was devastating to our family and to the community who had supported her. She was elegant, classy, beautiful and well-rounded. She was a woman of many talents, and within a year her life drastically changed. After a brief time, a divorce, and extended psychiatric care, I was able to spend time with her again, both supervised and unsupervised. It was great to have my mother back, and even though she was different, I was still able to enjoy her company and learn from her in more ways than I knew.

When I was 5 years old my mother developed late-onset schizophrenia. It was devastating to our family and to the community who had supported her. She was elegant, classy, beautiful and well-rounded. She was a woman of many talents, and within a year her life drastically changed. After a brief time, a divorce, and extended psychiatric care, I was able to spend time with her again, both supervised and unsupervised. It was great to have my mother back, and even though she was different, I was still able to enjoy her company and learn from her in more ways than I knew.

One of the things my mother and I shared was our passion to paint. During our visits, she would teach me about the most famous artists and their artistic techniques. One day we came across a 3.5 ft canvas, and she told me I should paint “Starry Night” originally done by Vincent Van Gogh. After a short time, I had finished the painting and she hung it above her couch. Everyone was so impressed that I finished this project, and my mother was especially proud.

However, one day, when my mother had a very bad episode of psychosis, she took a sharp knife and slashed straight lines down the entire painting, leaving it ruined and full of slash marks. I was so upset when she called to tell me it was the result of a break in. I knew better, but we both cried.

Everyone in my family understood how hard I worked, and what it meant to me and my mom. My sister tried to have it re-matted shortly after, but nothing would do the trick.

By this time, I was in college and decided that it was time to repair this painting, which still had not been thrown in the garbage. After a few days of thinking, I decided that like the doctor I wanted to be, I was going to actually hand stitch each slash with thick gold thread. When the stitching was finished, the painting took on a whole new light. It looked better! Not because it had repeated gold stitching down the slash lines, but because to me it meant that with any bad situation, sad, angry, depressed, or broken, there is always a way to move through it, overcome it, and “mend” a problem or wound that was once thought to be impossible. I was able to turn my mother’s illness into something that was positive, as this painting now hangs more beautifully than ever before. It is no longer “Starry Night”, a version copied from Vincent Van Gogh, or a painting ruined by my mother’s attacks of hallucinations and paranoia, but a symbol that no matter what bumps you hit along the road of life, there is always a golden lining and a way to overcome obstacles. I live my life by these ideals and always remember this story.

- Welcome to the Guild of Medicine by Curtis Stine M.D.

- Ted by Dennis Saver M.D.

- Shirley by Curtis Stine M.D.

- Making a Difference is.......

Welcome to the Guild of Medicine by Curtis Stine M.D.

Fogarty, faculty colleagues, parents and families, students and friends, I’m honored to speak with you today, and I promise to adhere to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s instructions for speakers: “Be sincere, be brief, be seated.”

First year students, welcome to the guild of medicine. Your formal apprenticeship will last at least 7 more years, but you will remain a learner for a lifetime. Even those who obtain “master craftsman” status continue to learn.

First year students, welcome to the guild of medicine. Your formal apprenticeship will last at least 7 more years, but you will remain a learner for a lifetime. Even those who obtain “master craftsman” status continue to learn.

But medicine is not technically a guild; it’s a profession. Members of a profession enjoy unique privileges, but also must assume unique responsibilities. Today, I’ll address one of the professional responsibilities of physicians: the responsibility of service.

What is service? The Gold Foundation defines service as “… the sharing of one’s talent, time and resources with those in need; giving beyond what is required.” Service is also a key element of the COM’s mission which concludes: “…especially though service to elder, rural, minority and underserved populations.”

One of the most quoted doctors of all time, Dr. Seuss, in his book, The Lorax, speaks of service when he says, “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

To parents in the audience who have been models of service to your children, thank you. Thank you for demonstrating the importance of service. As Thomas Jefferson said, “Every father should remember that one day his son will follow his example instead of his advice.”

My parents modeled service to me. My father was a physician who practiced for 38 years in a small northern-Indiana community. I remember asking him why he drove 9 miles into the country to make a house call on an Amish woman at 2 AM. This was his answer: “Her husband had to hitch up his horse and buggy and drive two miles in the dark to the nearest pay phone just to call me, so I knew she was sick.”

My father also volunteered at the county health department. The health department was 25 miles away, so once a month—after seeing patients all day—he drove 25 miles to the health department, saw patients from 7-10 PM, and then drove 25 miles home. My father understood that it was a physician’s responsibility to serve.

My wife, Linda, and I have tried to model service to our children. My oldest daughter and I tutored inner-city kids that attended a low-performing school. Every week, we drove to a church in downtown Denver, and met our students—an 11 year-old boy, Marco, and his 7 year-old sister, Yesica. These were bright kids whose parents spoke little English and hadn’t completed high school. We enjoyed helping Marco and Yesica with their homework, but we really enjoyed getting to know their families, their friends and their way of life. Service experiences can challenge our assumptions, point out our biases and blind spots, and bring us closer to people who are very different from ourselves.

Our family traveled to Juarez, Mexico, with a church group, to build a “house” for a local pastor who ministered to people living in the dump. The “house,” was actually a large shed, but it did have a concrete foundation and shingled roof, so it was the “nicest house in the dump.” When our group reached the building site, the adults started unloading materials and putting up walls, and our youngest daughter, Anna, began playing with some local children who were watching.

Anna later talked about the children she’d met. “They don’t have anything,” she said, “No shoes, no toys, no bikes, but they are always smiling.” What a great “life lesson”…that material possessions don’t assure happiness. Service + reflection = personal growth.

First year students, each of you listed service activities on your medical school application. Now that you’re here, will your service continue? Remember that the habits of service you establish now, will determine whether you are a “giver” or a “receiver” during the rest of your life. As Winston Churchill said, “We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give.”

There are many opportunities for you to serve. Talk with the new Gold Humanism Honor Society inductees about their service activities. As they can attest, you can excel in your studies AND do something significant to help others.

Fourth year students, I just gave some of you a “shout out” for your earlier service, but what your future service? Service opportunities will be there, regardless of your specialty choice. Who will become the pediatrician in Immokalee caring for children of migrant farm workers? Who will become a general internist at the Community Health Center in Orlando, caring for adults that fall below the poverty level? Who is going to deliver all the babies born in 2016 to single moms in Tampa? Who will become the family physician who devotes him/herself to serving a rural community in north Florida? Who will be my geriatrician as I retire, grow old, and eventually, die? To paraphrase the Talmud: “If not you, who? If not now, when?”

Serving others changes you…it makes you more compassionate, more appreciative and more self-aware. I encourage you to focus your career—either all or in part--on serving those in need. As my residency director told me, “Learning medicine is mostly about what you know; but serving the needs of patients is mostly about who you are.”

And finally, to my faculty colleagues—clinicians and non-clinicians alike. What are we doing to model service to students? How do we live out the service-oriented mission of the College of Medicine? To those clinicians who volunteer at facilities like Neighborhood Health Services, Refuge House or the Senior Center, thank you. To those who supervise student-run health fairs and service-learning electives, thank you. To you who volunteer as team physicians at local high schools, or serve on the boards of community organizations, your service is appreciated. As Dr. Albert Schweitzer said, “Example is not the main thing in influencing others. It is the only thing.”

I want to again congratulate our students. First year students: You’re off to a great start! Now, keep it up! Fourth year students: We are impressed by your academic accomplishments and by who you are becoming. And to both groups: I began with a quote from Dr. Seuss, but I leave you with another quote from Dr. Albert Schweitzer: “I don’t know what your destiny will be, but one thing I do know: the only ones among you who will be really happy are those who have sought and found how to serve.” Thank you.

Ted by Dennis Saver M.D.

I also welcome all of you here, as the students of the class of 2013 are first anointed with the uniform of their office. The White Coat acts to remind us of the professionalism and scientific approach required of a physician. These are crucial for competence, which is a necessary attribute. All of you in the Class of 2013 have already shown in your undergraduate careers that you are capable of achieving this kind of competence, and I have faith that you will continue to work hard and study hard during the next 4 years to earn the degree of M.D.

I also welcome all of you here, as the students of the class of 2013 are first anointed with the uniform of their office. The White Coat acts to remind us of the professionalism and scientific approach required of a physician. These are crucial for competence, which is a necessary attribute. All of you in the Class of 2013 have already shown in your undergraduate careers that you are capable of achieving this kind of competence, and I have faith that you will continue to work hard and study hard during the next 4 years to earn the degree of M.D.

I am very much honored to have been elected to the Gold Humanism Honor Society this year, which recognizes compassion and dedication to service, two additional elements of this profession. Today’s occasion provides an opportunity for me to address this crucial element of being a good physician: caring. Science and professionalism must be chemically bonded to caring, in order to make a really good doctor.

Both of my predecessors at FSU White Coat Ceremonies have quoted Sir Francis Peabody, and I will continue this tradition by reading to you his words:

“The good physician knows his patients through and through and his knowledge is bought dearly. Time, sympathy and understanding must be lavishly dispensed, but the reward is to be found in that personal bond which forms the greatest satisfaction of the practice of medicine. One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.”

It has been my life’s work in Family Medicine to use all the tools I have available to care for my patients. I need good science, committed public health, communications skills, psychological understanding, ethical guidance, and plenty of hard work to do the right kind of job. Medical training is tough…. and so is medical practice. There will be many lonely opportunities, when no one else is looking, to do less of a job than you are capable. However, if you are able to keep “caring for the patient” in center view, it will help you make the correct and professional choices. The healing that helps the patient takes place in the context of the patient-physician relationship. This relationship catalyzes good ingredients into a great product. In many ways, I believe that this relationship, this humanism, is not only the patient’s benefit, but is also the physician’s best reward.

All physicians have some special relationships, and for this address, I want to tell you about one of mine.

TED

Some people bring cold rain to one’s life, and others bring sunshine. Ted embodied the latter. He was already well into retirement when I met him, an unassuming gentle man living with his 2nd wife in a modest senior community. He was well liked by his neighbors, and friendly to my office staff. He had hypertension for many years, and COPD despite having quit smoking 30 years before. He shortly developed heart disease and I helped him through an MI, and the CHF that followed. During several hospitalizations, consultants did not engender his trust. Somehow, within a year or two, Ted bonded to me as if we had had decades of relationship. Whenever Ted and his wife Betty came to the office for a new problem or adjustment of an old problem, I would present therapeutic alternatives and options, but Ted would say “Whatever you think best, doctor.” And then he would do EXACTLY whatever I suggested.

Unfortunately, his road at this time of life seemed to have a pothole around every bend, as he developed atrial fibrillation requiring coumadin anticoagulation, renal insufficiency, and multiple skin cancers. If Efudex cream failed to remove a skin lesion, Ted would stop coumadin for 5 days and I would resort to curative cold steel, excising malignancies from his skin and placing them in small jars of formalin. Once, early on, I was overconfident of my hemostatic skills, and had him stop Coumadin only 4 days before a minor surgery. That night, he soiled a pillow, bed sheets, and several towels with bleeding. Betty had to do a lot of laundry, and she was there to tell me so……. Several times. I was more careful and more humble thereafter. I always double-checked with him before any local anesthesia started: “Ted, what day did you stop the coumadin?” He would give me the reply, and Betty would nod approvingly.

Ted, I discovered, had been the comptroller for American Airlines by the time he retired, after having worked for American for 30 years. He was very modest about having been a very very important fellow. He never spoke about it unless asked.

Betty’s daughter in Ohio was found to have breast cancer, and Ted spent a lot of time helping her. Later, when Ted was hospitalized for a colon resection for bowel cancer, both of Betty’s daughters flew to Florida to return the kind of emotional support that he had in the past provided to them.

Attachment has its virtues and its drawbacks. Ted and Betty worried about what might go wrong any time that I went on vacation or to a conference. His health was precarious enough that sometimes I would return to indeed find him hospitalized by one of my call partners. Living will and advance directive discussions are part of my once-a-year list of questions at an annual exam. Ted and Betty always maintained that when their days were over, neither one wanted to linger beyond what time was reasonable. Technology, ventilators, and so forth were for the living, not the dying. While neither was ready to fold their cards, and they were devoted to being with each other, each articulated a very straightforward view about the end of life.

Once kidney damage occurs from many years of hypertension, the course is often ordained. Ted’s creatinine was 2.1 when we met, and progressed to 3.2 by the time of his colon cancer surgery. With careful attention to anesthesia and avoiding fluid overload, he got through this hospitalization, although his creatinine hit 4.5. We talked about chronic kidney disease and dialysis, and I encouraged him to have a nephrology consultation. He consented with some reluctance; but since I recommended it, he dutifully agreed. The nephrologist found no problems that could be reversed, but no need for any immediate change in treatment. Eventually, however, Ted would need vascular access and dialysis.

Three months later, Ted’s creatinine had dropped back to 3.8 and he was ok, suffering through taking his complex regimen of medications, through monthly protime blood tests, and through slowly worsening fatigue. Every time I saw Ted, with Betty riding shotgun, or saw Betty, with Ted at her side, they were both embarrassingly grateful to me, thanking me for small things that others would not even think worth mentioning, wishing me good fortune or happy holidays, inquiring about my family. Ted and Betty felt like part of my family.

In the next 12 months, kidney function slowly declined further. Ted did go back to talk to the nephrologist once, but did not make any more appointments since he did not think dialysis was a good prospect for him at 83. Betty’s younger daughter died of her cancer, and he grieved. Betty herself underwent major surgery and a difficult convalescence, although she eventually recovered. They were indeed “frequent fliers” at my office, but seeing them was always an experience with positive emotions, no matter how intense were the medical management difficulties.

Even more skin cancers appeared, despite frequent use of Efudex cream. At the time of yet another minor surgical excision, Ted’s congestive heart failure had become impossible to manage as an outpatient, and he needed hospitalization for fluid overload and pulmonary edema. His creatinine was 6.0. He didn’t feel that bad, but he didn’t feel very good and had no appetite. We held a conference to review his circumstances. The decision was at hand: permanent dialysis, or no dialysis and death soon. This watershed decision was traumatic for Betty, who did not want to loose her husband, but neither did she want him to suffer. Ted reconsidered his prior choice, and saw nothing to warrant a change. He said “no” to dialysis.

The next days passed quietly, as Ted needed more oxygen and eventually morphine for his congestive heart failure and superimposed pneumonia. Close friends visited him briefly at regular intervals, and I talked with Betty daily for support and reassurance. Ted slipped into coma, then slipped away entirely, without visible suffering and in a very quiet and unassuming manner.

Betty grieved again, and handled the bad circumstances as well as anyone could. She went through Ted’s clothes about a month after he died, and donated them to charity. There were a bunch of suits, hardly worn, and crisp white shirts still in their wrappers. Later still, she brought me Ted’s last gift. He had kept little of all the memorabilia from his 30 year career at American Airlines, but he had treasured a small dish with the company logo given him at retirement, and had used it to hold pocket change. Betty asked me to keep it, to remember Ted by.

With Ted gone, there was not a lot to tie Betty to Vero Beach, Her remaining daughter encouraged Betty to move where she lived and could be of help. Betty realistically knew that her health would likely become more of a problem in the future, not less, and moving seemed the best option. My staff and I had a tearful goodbye with Betty and her daughter when the time came. Both were again grateful for the care I had provided and the relationship we had over a long span of time.

We got a couple brief letters in the next year, but I’ve not heard from Betty further. However, the memento American Airlines dish still sits atop my dresser, and Ted and Betty are still part of the family of my heart.

What does this story mean? It is about competent and complex medical care of multiple simultaneous chronic illnesses. It is about providing a broad spectrum of primary care (minor surgery, office and hospital visits). It is about coordinating care when provided by others. But most importantly, it is about having a deep relationship of honesty and trust between the patient and the physician. I am not so lucky as to have this depth of relationship with every individual I treat; nor will you be so lucky with all your patients. However, it is my goal to gain this kind of relationship, and I will work hard to build it. I encourage all the physicians-to-be of the Class of 2013 to strive also for relationships of caring. It is what I want from my doctor.

Shirley by Curtis Stine M.D.

Doctor, I’ve got this cough.

Can you prescribe something for me?

Help me feel better.

Doctor, that medicine you gave me didn’t work.

What do you hear in my chest? Pneumonia? Do you really think I need a chest X-ray?

Just give me an antibiotic.

Doctor, your nurse said you wanted to see me.

My X-ray was abnormal? What do you think I have?

Tell me I don’t have cancer.

Doctor, I can’t believe it.

How could I have cancer? Are you sure? Where did it come from? How did I get it?

Tell me I’ll be OK.

Doctor, I’m so confused.

How am I going to tell my husband? My kids? Our friends? The people at work?

You’ll talk to him, please.

Doctor, I want to see a surgeon.

You don’t think surgery would help? What’s an oncologist?

Get me an appointment as soon as possible.

Doctor, the oncologist wants to treat me with drugs.

What do you think? What would you do?

I’m going to beat this thing.

Doctor, my hair is falling out.

That means the drugs are working, right?

Tell me I’m going to get better.

Doctor, I’m losing weight.

Is that a bad sign? I’m not giving up.

Tell me what other treatments are available.

I don’t want to go to the hospital.

Who are these hospice people? Can’t you just see me at home?

I’ve got so many things to tell my husband; so many things to tell the kids.

Help me, won’t you?

Doctor, I’m so lonely.

Where are my friends? Where is my family?

Just stay a bit longer. You’re one of the few who haven’t deserted me.

Doctor, I’m having problems breathing.

Please, don’t let me smother.

Doctor, I’m in a lot of pain.

Please, make this pain go away.

Doctor, I’m so tired.

Please, I just want to sleep.

Good friend, I’m dying. We both know it.

Please, just hold my hand. Please?

Making a Difference is.......

Making a difference happens when we lose the lie we've been telling ourselves about our limitations, and then catalyzing that growth in others.

Making a difference happens when we lose the lie we've been telling ourselves about our limitations, and then catalyzing that growth in others.

Douglas J. Davies M.D.

Using our gifts as physicians to provide comfort and care to all patients regardless of their ethnicity, social status, or ability to pay.

Adam Bright M.D.

Really what it is ALL about.

Diane Wilkinson, M.D.

Preparing others to carry on, once I am gone

Elena Reyes, PhD

Often confused with a self-centered sort of demand that one’s value be noted and appreciated. Some who make the greatest difference in other’s lives are the least noted, and frequently least appreciated. Think of parents. Or think of what happens every time the garbage collectors go on strike in a big city. The effort should be to serve, and perhaps, years from now, you will be given the grace of knowing that a difference for the better was made.

Lisa Jernigan, M.D.

Why I am here at FSUCOM.

Karen Meyers ARNP

Restoring a child to health.

Jimmy E. Jones, M.D., MPA, FACS

Seeing a new person in need at the Neighborhood Health Services Center in Lincoln Center in on Brevard Street in Tallahassee Florida.

John Agens M.D.

Seeing the light bulb go off when someone suddenly understands how to help their own health

Bonita Sorenson

A life changing experience.

Tara L. Gonzales, M.D.

The only thing that really matters. It is an honor to have the opportunity to make a difference in our practice of medicine. It is what motivates the novice and the experienced healer to share their art with patients day after day.

Paul McLeod, M.D.

Inspiring others to make a difference.

Jeff Thill M.D.

Giving hope to those without hope.

Dr. S. Winters

Helping people to make appropriate choices.

Making sure my own house is in order first, by being the best dad and spouse I can be.

Curtis Stine, M.D.

Giving selflessly to those in need.

Rene Loyola M.D.

Spending a few extra minutes with a patient to listen to their story. The dialogue may be unnecessary for their care, but it is huge in building trust and rapport with patients.

Deanna Springer, M.D.

Becoming a whole person and sharing that with my patients and their families. It is realizing, as Abraham Heschl expressed so well, that "in order to heal a person you must first be a person."

Amaryllis Sánchez Wohlever, M.D.

Simultaneously thinking about the patient, “What exactly is the problem?” and feeling in your heart, “What must it be like to be going through that?”

Kenneth Brummel-Smith.M.D.

For me, as a physician, to be able to impact healthcare more than one patient at a time. I am challenged by how we better deliver effective care to frail elders. I chose a medical career because of needs I saw in nursing homes, but my patients want to stay home. How our communities more effectively support these patients and their caregivers through home and community-based long term care is where I’d like to help make a difference.

Donna Jacobi, M.D.

Making a difference is always knowing that a person can;

change the hearts, minds, and souls of man.

Sometimes easy, but often hard to do,

on the floors, in the clinics, and certainly in the ICU.

But be assured that now is always the right time,

to make a difference and to end this rhyme…

Benjamin M. Kaplan, M.D. MPH

Is treating each of your patients with the attention and care you would want to receive for yourself or your family.

Dr. Barbara Srur

Providing every child the opportunity to grow and succeed in life.

Gerardo Lopez, M.D.

When a patient tries to thank you, but rather starts to quiver and cannot form the words. But I can read the words through the tears in their smiling eyes.

David Billmeier, M.D.

Enabling the development of thought patterns that birth a change in action and enhance the creativity of solutions to a challenge.

Dr. Hansen

Is touching someone’s heart, not just their mind.

Chris Leadem PhD

Making a difference does not come just from doing your job well. It comes from extraordinary effort to care for others and to care about them. So at the end of the day, you can reflect " a small part of the world is a better place because of how I gave of myself".

Alan Forbes M.D. PhD

Standing up for an ideal and striking out against injustice.

Jerry Williamson M.D.

Acting as a change element, not just allowing something to continue as is. It is the decision to work for a change, to help someone with our talents, some folks say, "That's not right" but don't act to change the wrong. Making a difference can be listening to someone and sharing thoughts because you have been in that exact situation. Making a difference leaves behind a legacy of positive actions. Making a difference is when you know down deep you did the right stuff and you got a smile from a patient.

Joy Barbee BSN

Working at a community health center and creating a medical home for my patients is a big priority in my life. I enjoy reminding the moody teenager on the exam table that I once pulled a Lego soldier out of his ear! I have to remind the worried mother about how we got through the last fever that took 5 days to clear and that we will get through this. I feel sad when I see one of my adolescent girls across the hallway visiting with the obstetrician because she “promised” not to miss one birth control pill. On the other hand, I feel happy when she brings that baby to me because there is trust and loyalty. Being a pediatrician is an honor and a gift. It is being a mother to thousands of children with all the ups and downs being a parent entails. Life is good.

Dr. Anabella Torres

Is reaching towards infinity by teaching students who will teach their patients and other students who will teach . . .

Daniel J. Van Durme, M.D., FAAFP

Comes through living a productive and meaningful life.

Robert Watson M.D.

Is the legacy we leave

Anita Westafer, M.D.

Making a difference is the ultimate contribution to mankind.

Making a difference is what it's all about.

Making a difference makes life worth living.

Making a difference can impact countless numbers of people.

Making a difference can lead to positive change.

Michael S. Oleksyk, M.D.

- Irises

- I ration healthcare by José E Rodríguez M.D.

- So you think you can’t run? by José E Rodríguez M.D.

Irises

I Ration Healthcare by José E Rodríguez M.D.

Recently, I was asked to serve as the medical director of Neighborhood Health Services, a local charity run clinic, which primarily serves the uninsured patients of our community. We do not take any private insurance, Medicare, or managed Medicaid. Our premise is that if our patients have those benefits, the private physicians of the community could take care of them because they are paying patients. Most people that are seen in our clinic pay 5 dollars. If they do not have it, we generally see them anyway.

Our clinic is also affiliated with the local medical school, as well as the local pharmacy school. Medications are provided at a substantial discount, and those who are homeless, as well as many others can participate in programs that provide brand name medications at reduced or no cost.

Our clinic is also affiliated with the local medical school, as well as the local pharmacy school. Medications are provided at a substantial discount, and those who are homeless, as well as many others can participate in programs that provide brand name medications at reduced or no cost.

We live in a generous community. The physicians and other medical professionals have banded together to provide specialty and radiology care for uninsured patients. This program is based on volunteer providers—and they provide surgeries, radiological studies, and other procedures free of charge to those who qualify. I am touched by their generosity and grateful for what they are able to provide for our patients.

This week the USPSTF came out with a controversial recommendation: Mammograms are not necessary for women between 40 and 50. In this complex healthcare debate, this decision has been decried as “rationing,” and has been described as the harbinger of what is to come with any healthcare reform.

It is astounding to me that rationing is being so vilified. What is even more baffling is the fact that rationing is good enough for the poor, but not for anyone else. That is the ultimate in hypocrisy.

So you think you can’t run? by José E Rodríguez M.D.

Anyone can run! But somebody else already got that title. My title will be “So you think you can’t run?” This book is about running as an obese person, the exact kind of person that is not supposed to run. I will begin by telling my story—from the beginning. I was born in a small town in upstate New York, the 2nd of four children. My parents had recently moved from Puerto Rico, so they were living in a place that was unfamiliar to them. I of course, did not have any familiarity, because I was so young.

Anyone can run! But somebody else already got that title. My title will be “So you think you can’t run?” This book is about running as an obese person, the exact kind of person that is not supposed to run. I will begin by telling my story—from the beginning. I was born in a small town in upstate New York, the 2nd of four children. My parents had recently moved from Puerto Rico, so they were living in a place that was unfamiliar to them. I of course, did not have any familiarity, because I was so young.

As with most immigrant families, they were not accustomed to the Mainland US form of eating, and they tried to raise us with Puerto Rican food. That was difficult, because at the time, we were very far from New York City, the Mecca of all things Puerto Rican. As you can imagine, we ate as best as we could, and we worked hard.

They had purchased two acres in a small town, and they were determined to teach us the value of hard work. If you can imagine, we had 2 goats, 40 chickens, as many rabbits and 3 dogs. We lived off of the land, but we did work very hard. As a child I made a habit of feeding the dogs, changing the poop in the rabbit hutches and milking the goats every day after school.

Sounds like a rough life, but it wasn’t that bad. After a few years, I inherited a paper route and, with my father driving and my younger brother, we delivered about 70 papers to a rural community every single day before my father left for work at 5 am. It was real discipline training, which I have not forgotten. And it taught me my most important running lesson: Don’t be afraid of the dark!

We had a pool in New York, which we used from the day that it thawed in the spring to the day that it froze in the winter. We loved that pool, and every day in the summertime we were in it. I can remember that one of my brothers was born at the end of August, and before the pool froze that year, he was swimming with us in the water. We truly got our moneys worth out of that pool.

A few years later we moved to Miami, and it was always hot. The activities we did outside with the animals were no longer, as we lived in a smaller house with less property and more restrictions. The only physical activity I did there was one year of marching band—I quit after that for many reasons, discipline being one of them. We did have a pool, though, so I did not gain any weight.

Although I was not obese as a child, I always thought that I was fat. This is due to a genetic condition that many men share, but few are comfortable with. I have a big chest—and it is not from muscles. They are frequently referred to as man breasts. For me, they were always just fat. I thought that if I lost weight, I would not have them. So I was constantly trying to lose weight, but I never lost enough to lose the man breasts. But I was never fat—my BMI to my best estimate was no more than 24.

Then I went to college. I gained a freshman 15 (or was it 40?) and then took some time off. During that time I served as a missionary in Paraguay. Paraguay was a great time in my life. I walked everywhere for 2 years. I only infrequently rode bicycles and so I burned off the weight that I gained in my freshman year. I was not trying really to lose weight, but the combination of all of that exercise and the diarrhea made it so I could wear the same clothes that I had worn in high school. I returned from Paraguay at age 21 with a pretty lean frame. But that was the last time in my life that I was lean.

Upon returning to college I gained weight again. But this time there was no redeeming mission or exercise. I became fat, obese, or whatever you want to call it. My weight gain was over 3 years, but it was still significant—like 50 lbs. And with the weight gain, I lost my sensitivities about the man breasts. It turns out that all fat guys have them! So, I figured that I had reached the body weight that I should have.

Those were great times. I ate whatever I wanted and I continued to gain weight. I was comfortable with who I was and was happy that I did not have to diet, and in a good place because, like everyone else, I did not want to diet. During this time of intense weight gain, I met the girl of my dreams and we went out for many years. I did well in college and was accepted into a prestigious medical school. Things, I thought could not be better.

I started medical school at age 24. At the time, I lived in a medical school dorm. When I was in college I lived in a dorm as well, but this was something completely different. We each had individual bedrooms, and a bathroom connected every two bedrooms. The floor probably had about 20 bathrooms, so there were 40 people to each floor. We all shared a single community kitchen. I did not cook, and medical school did not lend itself to meal planning. So I began to eat out daily. The area where I lived in Manhattan was very expensive—the Upper East Side. Food was readily available, but the only “cheap” food, was of course McDonalds. At the beginning of the school year, McDonalds was 5 blocks away. I would go there at least daily because it was close and cheap. A month into school, however, and the store had closed. I remember how bummed out I felt, because I thought that the other McDonalds (10 blocks away) was too far to walk. It turned out that I had no reason to fret because a McDonalds opened up on the same block where I lived, making the walk there and back less than one block. Then I began to eat all three meals at that McDonalds. I ate the double cheeseburger meal, and I put the fries inside of the burger. I loved Big Macs and tried to eat them twice a day. I usually skipped breakfast because I never had time for it. Years before supersize me, I was eating Morgan’s diet. And I truly had no idea that it was bad for me.

A few months later I married my college sweetheart. That abruptly ended the McDonalds trips, as she was an excellent cook and she ate and prepared healthy food for the both of us. I did not have a spare second for anything, so I did not exercise—it was a great excuse. It seems medical school was all studying all the time. I must have had some recreational time, because during my second year of medical school my oldest son was born.

After my son was born, I had the revelation that I was not the only person in the universe. It turns out that women know this fact their whole lives, but men seem to discover it after they become responsible for someone else—usually a child. I knew I had to provide for him and his mother, but I was unsure how. I had a very small (in retrospect) medical school debt, but I was still concerned about our future. Having no concept of physician salaries or how much it costs to live, I became desperate to get more money. A colleague of mine told me he was thinking of joining the navy, and he invited me on his recruiting trip. It was a great trip! They paid for our flight to Norfolk Virginia, and we were able to see first hand what Navy physicians did. I was enamored of the idea, and I asked for the papers so I could sign up. The recruiter said something to me, but all I heard was, “José, you are too fat.”

Medical school is not for the faint of heart, and since this was near the end of the experience, I was feeling fairly confident that I could do anything. (A misguided feeling at best—but it was more likely a delusion). I told the recruiter that I wanted to join, so she needed to tell me how much the maximum weight was for physician recruits. I remember her telling me that it was 30 lbs. I told her that I could lose it, and that I would contact her when I did. She promised that if I lost the weight, I would qualify for the program, which would pay all of my debts, give me extra money during residency, and a job when I finished residency. The seduction of security was too much to resist. I bought a commercial weight loss diet and I lost 30 lbs in 30 days. Those thirty days, however, proved to be a time of transition. The pull towards the Navy was not so great, so I called the recruiter, told her that I had lost the weight, but that I was not ready to commit to the Navy.

I was very proud of myself! I had never tried to lose weight before, and with the help of the diet, I did it with relative ease. However, it was not to last. That business about a freshman 15 is nothing compared to internship. The lack of sleep alone was enough to drive a man crazy. Because of certain religious commitments, I do not drink coffee or anything that has caffeine. So not only was I sleeping deprived, I was deprived without a means to stay awake. So I turned to food.

As interns, we received very generous meal allotments for the times that we were on call. At the time, my colleagues would always have extra meal tickets at the end of the month, so they would share them with me. I found myself eating out very often. I remember that my favorite food was a bacon grilled cheese sandwich that I ate when I was on call, between 2 and 3 am. If I was lucky, I would get some sleep, and then I would have a huge breakfast of bacon, eggs, cheese, pancakes, toast and orange juice. While the food did nothing good for my weight, or my cholesterol, it did keep me up.

After my internship year, I had gained 60 lbs—the 30 that I lost plus thirty more! The weight gain did not bother me either. This is probably due to the unique wardrobe that beginning doctors wear. The hospital where I worked provided scrubs for us to wear. They do not come in numbered sizes, just small, medium, large, and extra large. And they do not hug your figure, or make anything look big or small. They are fairly ugly clothes, built for comfort. To top it all off, you wear a white lab coat over it, so if you are growing where you don’t want to, you are the only one who can see it. So I gained weight and I could not care less. But all of that was about to change….

After three years of scrubs and coats to hide behind, it was finally time to graduate from residency. As you can imagine, it is a big deal, because it is the one experience in a doctor’s academic career that really means never having to do it again. We have to take tests throughout our career, we need to keep up by reading and writing journal articles, but most of us will never have to repeat residency. Naturally, my parents came to celebrate with my wife and kids. My father, in passing, mentioned that he would like a physical exam to go to scout camp. I told him that I would do it and I took him to my office. I was very clear with him. I would take his pressure and fill out the form for his camping trip, but if I found anything that bothered me, he had to promise me to go to his physician and get it taken care of.

On his physical I discovered that he had hypertension, at a level that sound medical practice demanded treatment with medication. He, of course, was looking for another way—any other way—to lower his blood pressure. He has always detested pills and I knew that I was the only person who could help him make the decision to take them. We spoke at length, and he finally agreed to start taking medication. In his search for an alternative, I spoke with him about diet and exercise changes. I talked a lot about exercise because I had read somewhere that consistent aerobic exercise in the morning could help control blood pressure for the whole day. and alternative therapy that makes your pressure go down. I talked to him at length about exercise, but it did not have the “ring of truth.” In other words, I was suggesting something to him that I myself was not doing. I also was 66 inches and 224 lbs. (BMI of 36).

Fast forward 2 months and 9-11-2001 happened. All of us have had to cope and deal with this horrific event, which at the very least produced more stress in our lives.

The day of Thanksgiving, 2001, I got a telephone call from my mother. My grandfather was ill and we had told her that if he died, we would go to the funeral. The call was of course, the bringer of that bad news, so we got tickets and went to Puerto Rico. He was 89 years old and always the healthiest person in the family. After the funeral, I had asked my grandmother what she was going to do with his old medications. She told me that I could have the medicines. As I was going over them I discovered that my grandfather had Diabetes Type 2. I was surprised, because they had always told me that there was no diabetes in my family. I later learned that he developed it at age 84. At the time I thought 84 would be a nice age to develop diabetes. The fact that he had diabetes really hit me hard; I had just learned that my aunt also had diabetes. She however, was much younger, and I did not want to have diabetes when I got to her age of diagnosis.

Diabetes, Hypertension, stress, a new job….all of it was coming due. 2 more months go by and a friend of ours from church asked me to go to their house to pick up a toddler bed, and an air conditioner. I picked up those things and asked about their exercise bike. They said I could have it if I would use it. I told them that I would use it, but that it may take months. And I took the bike.

In March of 2002, I attended the National Hispanic Health Association meeting in Washington, D.C. I also attended a seminar on Diabetes, and what we could do about it. By this time, I had learned that exercise would help for sugar control, but every time some one would ask me how to do it, I would just say it was a “challenge” and very difficult. I can remember the presenter, but I cannot remember her name. She was however, thin. And then she showed us her pedometer. For me that was a pinnacle moment—thin people have to exercise too!!! I had no idea that they did. I was fascinated by this pedometer, and was inspired by that meeting.