When the smoke clears - the damage may be more widespread than you think

College of Medicine research examines scope of damage from smoking during pregnancy

The deleterious effects of using tobacco products while pregnant are well established, though e-cigarettes and vaping have created confusion on that topic for some.

Far less attention has been devoted to the damage nicotine creates beyond the mother and the child in her womb.

Florida State University College of Medicine researcher Pradeep Bhide is studying the risk of nicotine exposure causing neurodevelopmental effects that are transmitted to future generations. He recently was awarded a $627,000 grant from the Florida Department of Health’s James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program for his study, “Nicotine, germ cells and neurodevelopmental disorders.”

“Nicotine use by pregnant women increases the risk for behavioral disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder and drug addiction in their children. These consequences often attract less attention than the more widely recognized consequences for the mother, namely increased risk for cancer and cardiovascular disease, and the consequences for the children, namely pulmonary and immunological disorders,” said Bhide, professor and Jim and Betty Ann Rodgers Eminent Scholar Chair of Developmental Neuroscience.

“However, behavioral disorders contribute to significant personal, educational, economic and health-care costs. Recent studies show that the adverse neurodevelopmental effects of nicotine exposure may not only be manifested by the individuals exposed to nicotine in the womb but may also be transmitted to their descendants in multiple generations.”

This “transgenerational transmission” of nicotine’s harm may impact a population two to three times greater than current estimates, Bhide said.

Bhide and colleagues – Deirdre McCarthy and Lin Zhang from the Department of Biomedical Sciences and Cynthia Vied from the Translational Science Laboratory – utilize a mouse model and equipment capable of delivering e-cigarette nicotine exposure consistent with the exposure humans receive when smoking. Bhide’s work will be in collaboration with Gloria Salazar, associate professor of Nutrition, Food and Exercise Science at Florida State.

He was particularly interested in e-cigarette exposure, including vaping, because there is growing evidence that many women who smoke believe they are OK to switch to e-cigarettes after they become pregnant without harming their unborn child.

“The importance of understanding all of the health effects for e-cigarette use is vital given the rise in use and nicotine amounts, their potential to induce multiple functional deficits in the offspring of users as a result of an alteration in the fetal epigenome,” said Jeffrey Joyce, senior associate dean for research and graduate programs at the College of Medicine. “This grant will allow research to focus on the functional and epigenetic impact of in-utero exposure to maternal e-cigarette smoke.”

Bhide notes that when e-cigarettes were introduced, they contained a fixed amount of nicotine – in some cases less than what is found in a typical cigarette. Now e-cigarettes contain more nicotine than combustible cigarettes, and some e-cigarette products allow consumers to add as much nicotine as they wish.

“The goal is to find out what happens to the child that is born – or mouse, in this case,” Bhide said. “And to see if only the person exposed in the womb has these deleterious behaviors and brain changes – or does that pass on to the future generation?”

Bhide and his lab are looking at the mouse’s behavior to assess attention span, working memory, hyperactivity and cognitive flexibility, a measure of the brain’s ability to adapt to changing signals.

The team also then looks within the brain to examine and measure neurotransmitters and gene expression.

“There are certain molecular changes in the brain that allow us to see if what we find in the behaviors is represented by corresponding changes in the expression of genes,” Bhide said.

“One of the exciting things about this research is that, of course we know nicotine alters germ cells, but what exactly it alters is not presently known. There has been a belief that long-term exposure to smoke probably produces changes in germ cell DNA, but that those changes are temporary, or that they go away when the smoking stops.”

Instead, Bhide hypothesizes that the changes in germ cells of the individual exposed to nicotine in the womb are not temporary, but that at least some are permanent, epigenetic changes that will correlate with what is found in the brains of the next generation.

A number of human studies have utilized transgenerational health records to compare behaviors in children with what is known about the smoking habits of their grandparents. Those studies have shown an increased risk of ADHD-related behaviors for children whose grandparents smoked.

Bhide’s team also recently published a study showing that when a father smokes, his children have a greater chance of ADHD-related behaviors. Previous studies focused more on the impact of a mother smoking during pregnancy than on any impact the father’s behavior may have.

“Mouse model findings are consistent with what has been found in human studies, but the mouse model allows us to go further by looking at genes and neurotransmitters in the brain,” Bhide said.

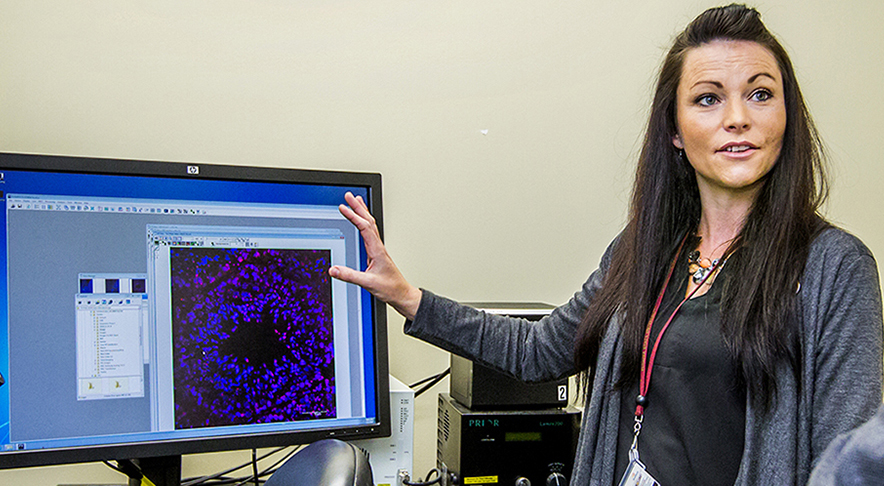

Photo (this page): Deirdre McCarthy, College of Medicine research faculty.