New med students try on their white coats

August 2014

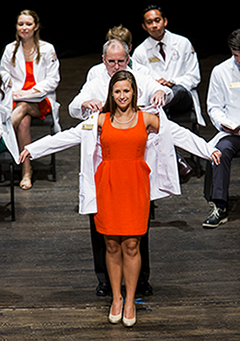

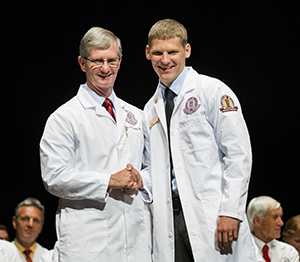

Though they’ve completed only one semester and have eight more to go, the College of Medicine’s newest students look more like physicians than ever — because now they have their white coats. They received them Aug. 22 at the White Coat Ceremony, in front of family, faculty and friends at Ruby Diamond Concert Hall.

“This ceremony serves as a reminder that you are not just going to school — you are joining a profession,” Dean John Fogarty told the students of the Class of 2018.

Also that evening, the Gold Humanism Honor Society chapter inducted its newest members.

White Coat is similar in some ways to commencement. Instead of being “hooded,” though, participants are “coated.” That is, they walk onstage and a faculty member (or family member) helps them put on their spotless white coat. Like commencement, White Coat blends the formal and informal. At one point, for example, the students recited an oath to “dedicate my life to the service of humanity.” At other points, babies were crying and families were shouting out support for their favorite doctors-to-be.

This year, except for Fogarty’s introductory remarks, the speeches came not from veteran teachers but from a fourth-year student and a recent alumna.

Jonathan Salud, a Class of 2015 Gold Humanism honoree, smiled as he told the new students that over the summer they had “built up a nice little anthill” — compared with “the mountains and mountains of knowledge yet to come.” Through anecdotes based on his clinical experience so far, he explained that humanism is “the difference between simply providing care to, versus actually caring for, our patients.”

Jonathan Salud, a Class of 2015 Gold Humanism honoree, smiled as he told the new students that over the summer they had “built up a nice little anthill” — compared with “the mountains and mountains of knowledge yet to come.” Through anecdotes based on his clinical experience so far, he explained that humanism is “the difference between simply providing care to, versus actually caring for, our patients.”

The main speaker was Abby (Hunter) Peters, who graduated from the College of Medicine in 2011, received her pediatric residency training at Wake Forest and has just returned — along with her husband, classmate Jeff Peters — to practice in Tallahassee.

She told of the time she cared for a 3-year-old boy with a congenital condition that eventually took his life. At the funeral the boy’s father embraced her and thanked her for taking such good care of his son. At first she wondered how he could thank her, given the sad outcome. Upon reflection, though, she saw things differently: “In this moment, it was not about being a highly trained medical professional. It was about being willing to be genuinely human with a mother and a father who adored their child…. Yes, I had cared for his son medically. But I believe our time spent together in prayer, celebrating victories over the disorder, and seeing his little boy filled with joy, and us joyful with him, mattered more.”

Here is a sampling of Peters’ other comments to the first-year students:

Here is a sampling of Peters’ other comments to the first-year students:

- “I feel fortunate to have trained at a medical school that fosters, nurtures and develops compassion, empathy and dedication to the community.”

- “Some of you may be stepping into this journey with trepidation, wondering if you have what it takes. Let me assure you that each of you has been carefully chosen because you have the exact talents and characteristics to succeed in medical school. And not just to succeed, but to

be great.”

- “Your ability to touch lives starts right now.”

Read the rest of Abby Peters' speech below.

THEY CELEBRATED AT TMH INSTEAD

THEY CELEBRATED AT TMH INSTEAD

If you have to miss the White Coat Ceremony, you’d better have a good excuse. Andrea Ramirez had one of the best: appendicitis.

Her parents, Ramiro and Olga Ramirez, had left Winter Haven that Friday and were about an hour and a half from Tallahassee when the phone rang. “Turn around,” their daughter said. “I’m in the ER!”

Of course, they didn’t turn around. After all, Olga is a nurse – and her daughter was suddenly a patient. Andrea’s doing fine now. But on White Coat Friday, TMH was host not only to her but to a roomful of visitors: 12 of her family members who had traveled here for the ceremony.

One week later, Andrea’s parents drove to Tallahassee again. This time, they came to the College of Medicine. With their other daughter Brenda looking on from Bartow via FaceTime, Dean John Fogarty coated Andrea, and together the two of them read the oath that the other students had read during the ceremony.

The dean also asked her: “Did my Grand Rounds lecture on abdominal pain help?” Smart student that she is, Andrea gave the perfect answer: “Yes, it did. I diagnosed myself!”

Her surgeon, it turns out, was Dr. Wade Douglas – who recently was named to head the new FSU surgical residency program at TMH. And Andrea is thinking that she might like to become a general surgeon.

First things first, though. At least she has her white coat now.

IT’LL BE A THREE-M.D. FAMILY

For some students, receiving the white coat is more than a symbol of their commitment to medicine — it’s a symbol of family bonding.

For some students, receiving the white coat is more than a symbol of their commitment to medicine — it’s a symbol of family bonding.

Growing up in Stuart, Ryan Suits knew he wanted to be a doctor. “I always saw how happy patients were when they left my parents’ office,” he said. (His parents, Drs. Thomas Suits and Irene Machel, who work together in a urology practice in Stuart, are part of the Fort Pierce Regional Campus clerkship faculty.) “I grew into feeling that I wanted people to have that same happiness and help them the way my parents helped them.”

So he, too, is pursuing medicine. At the White Coat Ceremony, the first-year College of Medicine student was coated by his mother.

“My parents had to play rock-paper-scissors over who would put my coat on,” he said, “but I think my mom thought it would be extremely special.”

He was right. “It was just heartwarming,” his mother said. “Incredibly special. It’s something that he’s wanted for so long, and to see him accomplish it was fantastic.”

The audience agreed, with an audible “Aw” when the two hugged onstage — marking the new bond Suits now officially shares with his parents.

NEW GOLD HUMANISM INDUCTEES

NEW GOLD HUMANISM INDUCTEES

Before the first-year students slipped on their new coats, they got a vivid image of where they might be in three years. They watched 14 members of the Class of 2015 inducted into the Gold Humanism Honor Society.

“We do this at White Coat to both honor them and to demonstrate to you, our freshman

class, that becoming doctors is not just about book knowledge but is also in the

professional behaviors, attitudes and attributes that are embodied in these students,” Fogarty told the audience. “We frequently think of these honorees as future ‘doctor’s doctors’ — the highest praise you can imagine, to be asked by a colleague to be their personal physician.”

The inductees were Amanda Abraira, Ryan Berger, Tyler Caton, Nicole Dillow, Maria Paula Domino, Brian Gordon, John Hales III, Shermeeka Hogans-Mathews, An Lawrence, Joanna Meadors, Patrick Murray, Sarah Ashley Robbins, Jonathan Salud and James Tyler Zorn. Maureen Bruns and Yaowaree Leavell were also chosen but couldn’t attend that night. They’ll be inducted later.

Daniel Van Durme, faculty sponsor of the Gold Humanism Honor Society chapter, explained to the audience: “Most medical schools in the country have now adopted the concept of teaching patient-centered medicine — not disease-centered and not doctor-centered, but truly focused on serving the unique needs of the patient. Humanism takes it even further. Humanism includes attributes such as compassion, service, integrity and respect.”

ABBY PETERS’ SPEECH

… I am truly honored to be here this evening and have never addressed an audience more important to me than this one. The students represent the future of medicine. Tonight, we are here to witness you symbolically join this noble profession by donning your white coat. Today you become part of a tradition: the physician as a servant of the sick. Your ability to touch lives starts right now. Never doubt that you can make a difference.

You have made two great choices: medicine and Florida State. One of our very own attending physicians, Dr. Stine, once shared with me that medicine was the most interpersonally and spiritually rewarding profession he could imagine. I must admit — I agree.

As a graduate of this medical school, I can assure you that Florida State will give you the tools to become an incredible physician — dedicated to a professional calling. The one-on-one patient and attending time we experience at FSU is second to no other medical school in the country. As a student, I was unaware of just how brilliant our medical training model is. Being an important part of the medical team as a student is, in fact, unique. It was through this notable autonomy and responsibility that I followed my heart to the specialty of pediatrics as a fourth-year student.

As a graduate of this medical school, I can assure you that Florida State will give you the tools to become an incredible physician — dedicated to a professional calling. The one-on-one patient and attending time we experience at FSU is second to no other medical school in the country. As a student, I was unaware of just how brilliant our medical training model is. Being an important part of the medical team as a student is, in fact, unique. It was through this notable autonomy and responsibility that I followed my heart to the specialty of pediatrics as a fourth-year student.

It was Day One of my PICU rotation and a little girl was airlifted to us for a drowning event. I remember looking at her lifeless body and praying quietly to myself for a miracle. However, as we put in lines, reviewed blood gases and struggled to maintain her vital signs, I was left with a deep sense of human fragility. My attending physician gave me what at the time I thought was an incredible burden but, looking back, was the opportunity to be very independent with a family in need of support. To be able to tell this family that “although your little girl’s life on earth was short, she touched so many lives, including my own” is an experience I will never forget.

I feel fortunate to have trained at a medical school that fosters, nurtures and develops compassion, empathy and dedication to the community. Unknowingly, you will gain a skill set over the next four years that most physicians learn in residency and beyond. When you leave FSU to begin your residency training, the confidence and comfort with which FSU graduates care for patients and families is acknowledged early on. You will be competent, courageous, enthusiastic, professional and well-equipped to take on the next part of your career.

I believe the White Coat Ceremony is a time to recognize the wonderful human attributes associated with the medical profession. As a way to do this, I would like to ask you to reflect with me about the kind of doctor you want to be. By this I do not mean the specialty you may enter (although pediatrics is great!), but rather the humanistic qualities you would like to have as a practicing physician. I will give you a few ideas to consider.

- Be a doctor who learns from and respects all members of the health care team, including the most important member: the patient. Allow your patients and their families to teach, humble and inspire you. I kept a journal during medical school and, in preparing for this ceremony, reflected on various influential moments. The excerpt I will share with you now is from my first trip to Filipina, Panama, in 2008 with FSUCares. “It was the last day of clinic and a sweet older lady with a gentle spirit sat in front of me. She had no real complaints other than minor aches and pains. I felt inclined to let her know that she was strong and had a beautiful smile. At the end of our encounter, she grabbed my hand and with tears in her eyes said, ‘Thank you.’” Thank you. These are two very simple words, often taken for granted. However, I can tell you the sincere gratitude and happiness emanating from her words made a lasting impression on me. Patients will thank you … for your kindness, dedication, time and interest. I encourage you to never let these two words become commonplace. They are intended to be a sign of gratitude and respect. Take the time to recognize the importance of your work and to remind yourself that practicing medicine is, in fact, a privilege. For you have been given a unique skill set and have the opportunity to add quality of life to those around you.

- Be humble. We will never respect others if we consider ourselves superior to them. I have a strong interest in caring for children with special health care needs. However, even with this interest, I confess that at times I judge. Questions regarding true quality of life, burdens placed on families, and morality in pursuing endeavors to extend the inevitable have all raced through my mind. It is human nature to judge, but I encourage you to evaluate difficult or special patient populations outside of the medical setting. As a resident, I had the opportunity to volunteer at Victory Junction, a camp for children with special health care needs. After spending one week in a cabin with adolescent girls with cerebral palsy (most of whom required great assistance with bathing, dressing, grooming, eating and taking medications), I walked away rejuvenated and with the utmost respect for these girls and what they contribute to the world. They may not have had perfect bodies, but they had perfect hearts that we can only strive to emulate. Similarly, I volunteered with a group of 7- to 8-year-old girls with HIV. I have never in my life been more overcome by a group of children. Volunteering with little girls who had to adhere to difficult drug regimens and face the stigma that comes along with living with HIV through no fault of their own was challenging. However, the only images I remember are their smiles and how they chose to live life courageously. One little girl who was wise beyond her years shared with me that she wanted to “leave a legacy of not how the world is, but how the world should be.”

Be a doctor who understands and is proud of what you know but, more important, recognizes what you don’t know. While you will cure many patients during the course of your career, you will also be involved in the care of patients with illnesses you cannot cure. Remember that even in these situations there is always something positive you can do for every patient. Over the past three years, I have had the opportunity to work with exceptional children and their families. Each family has a unique experience in confronting illness and its treatment. However, the honesty, dignity and hope with which children and families face indiscriminate disease have truly been an inspiration to me. During my training, I cared for a 3-year-old boy with a congenital glycosylation disorder, an inherited condition that affects many parts of the body. After battling pneumonia for four weeks, he passed away in his mother’s arms at 4 a.m. on a Friday. I had developed a strong bond with this family and was able to attend his funeral. Following the service, his father embraced me and said, “Thank you for taking such good care of my son.” Crying, I was taken aback by this comment. His son had passed away and he was thanking me? However, as I reflected upon this father’s words, I recognized that in this moment it was

Be a doctor who understands and is proud of what you know but, more important, recognizes what you don’t know. While you will cure many patients during the course of your career, you will also be involved in the care of patients with illnesses you cannot cure. Remember that even in these situations there is always something positive you can do for every patient. Over the past three years, I have had the opportunity to work with exceptional children and their families. Each family has a unique experience in confronting illness and its treatment. However, the honesty, dignity and hope with which children and families face indiscriminate disease have truly been an inspiration to me. During my training, I cared for a 3-year-old boy with a congenital glycosylation disorder, an inherited condition that affects many parts of the body. After battling pneumonia for four weeks, he passed away in his mother’s arms at 4 a.m. on a Friday. I had developed a strong bond with this family and was able to attend his funeral. Following the service, his father embraced me and said, “Thank you for taking such good care of my son.” Crying, I was taken aback by this comment. His son had passed away and he was thanking me? However, as I reflected upon this father’s words, I recognized that in this moment it was

not about being a highly trained medical professional. It was about being willing to be

genuinely human with a mother and a father who adored their child. As physicians, we have the

opportunity to bear the burdens of others. True love is shown when we bear one another’s burdens, when we help each other in hard times, and when we get involved in each other’s lives. Yes, I had cared for his son medically, but I believe our time spent together in prayer, celebrating victories over the disorder, and seeing this little boy filled with joy, and us joyful with him, mattered more. Being able to be present and to help patients at the end of life is both a great gift and a great responsibility.

Over the next four years you will learn to take a comprehensive history, perform a careful physical exam, obtain appropriate diagnostic tests, and develop accurate assessments and plans. Some of you may be stepping into this journey with trepidation, wondering if you have what it takes. Let me assure you that each of you has been carefully chosen because you have the exact talents and characteristics to succeed in medical school. And not just to succeed, but to be great.

Yes, competency is the most important aspect of being a physician, but beyond being competent, I encourage you to look outside of the diagnosis and treatment and realize your purpose might be to hold a hand, to engage in a friendly conversation, or to help a family through the grieving process. And the good news is that at Florida State you will know your patients well enough to feel comfortable doing so. Do not take these moments for granted. These experiences provide humility and perspective.

I will close by saying it is worthwhile to reflect upon why you have chosen medicine as your career. Each of you has been influenced by family, friends and mentors. They deserve your lasting gratitude. Many of my role models are sitting right behind me. I cannot express to you enough how invested the College of Medicine faculty are and how much they truly enjoy seeing us make the transition from books to clinical medicine. I am very proud that you are here and wish you every success in your training and in your life as a physician.

I will leave you with one of Dr. Van Durme’s favorite quotes and one that I reflect upon often: “I don’t know what your destiny will be, but one thing I do know: The only ones among you who will be really happy are those who have sought and found how to serve” (Dr. Albert Schweitzer).

Thank you for your time, and congratulations.