First-year students don white coats

By Ron Hartung

Aug. 22, 2011

The official wardrobe of the Class of 2015 now includes 119 white coats. At an inspiring ceremony Aug. 19, the first-year College of Medicine students pledged to dedicate their lives to serving humanity and slipped on their new coats, symbols of the medical profession.

Students Robyn Rachesky, Saritha Tirumalasetty and James Zorn were each helped into their coats by one of their parents, members of the College of Medicine’s clerkship faculty.

Robyn Rachesky is coated by her mother, Dr. Ingrid Rachesky, a clerkship faculty member. |

|---|

Watching and cheering this rite of passage were relatives and friends so numerous that they filled Ruby Diamond Concert Hall. Afterward, a sea of white coats and proud parents encircled the fountain in front of the Westcott Building for the ultimate family photo op.

Also honored at the ceremony were 12 members of the Class of 2012. Based on nominations from faculty, staff and fellow students, they were inducted into the Gold Humanism Honor Society and saluted for having the ideal blend of knowledge and compassion. Those students were Kate (Cleary) Alonso, Natasha Demehri, Laura Diamond, Aaron Hilton, Brett Howard, Demetrios Konstas, Brandon Mauldin, Diana Mauldin, Ricardo Sequeira, Michael Silverstein, Elise Switzer and Helen Travis.

Speaking to the first-year students, fourth-year student Demehri passed along hard-won wisdom from a time during clinical rotations when her private and professional lives collided. “I never thought that the first patient I would lose would be my friend,” she told them. It was a moving story. (Read it on Pages 30-31 of the summer issue of FSU MED magazine.)

Among her other messages to the new students were these: “You have little to lose, and everything to gain, by letting a sick person into your heart…. What is humanism in medicine? It’s simple: It’s a relationship between two human beings, one of whom – you – happens to be a doctor.”

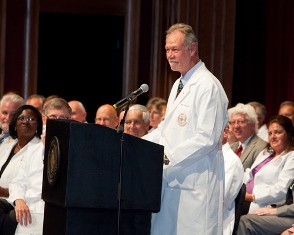

The evening’s featured speaker was Dr. Paul McLeod, senior associate dean for regional campuses, and dean of the Pensacola campus. He urged the new students to be willing to laugh at themselves – then invited them to laugh at him by telling tales of his own rookie shortcomings.

On one occasion, he said, “I encountered a young lady in the emergency department with a complaint of a swollen jaw. Having just finished studying diseases of the oral cavity, I thrust myself into a barrage of questions intended to uncover her occult dental abscess or her salivary gland tumor…. I gave a comprehensive presentation to my supervising resident. Appearing totally unimpressed by my efforts, he accompanied me back to the patient’s room…. He flung open the door, glanced in her direction and asked one question: ‘Someone hit you, ma’am?’ ‘Yes.’”

Here are the Class of 2012 Gold Humanism Honor Society inductees. |

|---|

He also told a poignant story about a patient who was much too sick much too early in life – and how he wrestled with the questions of “Why her?” and “What if…?” and “Why didn’t I do something sooner?” (For the surprise ending to that story, watch the White Coat Ceremony video, starting shortly after the 1:05 mark. Or read Dr. McLeod's speech below.)

College of Medicine Dean John Fogarty thanked all who attended for supporting their favorite students – and jokingly warned the families not to seek medical advice from them just yet. He also encouraged the students to wear their white coats with pride.

“This ceremony serves as a reminder that you are not just going to school – you are joining a profession,” he said. “Ceremonies provide opportunities to commit or recommit to the oaths, vows and traditions of our profession.”

He reminded the first-year students that they have eight semesters of medical school remaining. But they have one completed, and now they have their white coats. It’s been a big summer.

The White Coat (Speech delivered by Dr. Paul McLeod)

It is indeed a pleasure to share this time of celebration and contemplation with you today in the presence of your peers, families, friends and faculty. My fellow regional campus deans and I look forward to welcoming you to one of our communities in a few short years. Rest assured that you will be very well prepared for the transition.

You have not arrived here by accident, nor entirely as a result of your own efforts. For all of you were gifted with the ability to master the demanding educational requirements of the next four years, a task that looms larger than life to you right now. You were also given the gift of opportunity -- an opportunity that many other highly qualified young people were denied. Now it is up to you. To those whom much is given, much will be required. No doubt, you will all run valiantly with the torch that you have been handed.

The white coat has a unique meaning to each of those who are touched by it. To patients it represents the profession of medicine. It is a comforting symbol of hope and healing that reflects the legacy of those who came before us. The obligation to pay it forward now rests with you. You have exchanged a life of trivial pursuits for one of service. Your success in medicine will not be measured by your accomplishments, but your significance. By donning this coat you have declared that life is not about you. That you were not put on this earth to be remembered, but to heal when you can and comfort always. Along the way life’s circumstances will remind you time and again that you are a human honored to serve other humans. The mental and physical rigors of this profession will weigh heavily upon you at times. You will have personal needs that go unmet. Your family will as well. Often you will need to feel the gentle hand of a loved one on the shoulder of your white coat.

Dr. Paul McLeod was the featured speaker. |

|---|

Your experiences in the next four years will shape you. Some will change you forever. There will be a time for humor; seek it. There will be a time for heartache; it will seek you. Laugh whenever you can. Laughter is a cathartic that prevents us from taking ourselves too seriously. During medical school, I had many opportunities to laugh at myself, so bear with me a few minutes as I share with you some experiences witnessed by my white coat.

As a third-year student on the medicine service I was sent to evaluate an elderly lady with abdominal pain. The rectal exam confirmed my biggest fear, a classic apple core lesion of colon cancer. The mass was firm and ominous. I summoned my intern to share the devastating news and demonstrate my advanced physical exam skills. He reluctantly repeated the exam and began to walk away, shaking his head in disbelief. “You felt it?” I asked. “I sure did,” he replied. “Congratulations, McLeod, you found her cervix.” Definitely not an honors performance.

On another occasion I encountered a young lady in the emergency department with a complaint of “swollen jaw.” Having just finished studying diseases of the oral cavity I thrust myself into a barrage of questions intended to uncover her occult dental abscess or salivary gland tumor. Alas, my gallant scholarly effort was to no avail. Nonetheless I gave a comprehensive presentation to my supervising resident. Appearing totally unimpressed by my efforts he accompanied me back to the patient’s room. I followed in the shadow of his white coat. From the hallway he flung open the door, glanced in her direction and asked but one question: “Did someone hit you, ma'am?” “Yes,” she replied. How I made it through I will never know. I can see some of you scribbling a note to yourself: "Don’t go to Pensacola campus."

When you enter practice the white coat will accompany you. Your career will be filled with stories. Many of them will serve as a reminder of the priorities that we should have in our own lives.

One evening, seven years ago, I received a call from a young woman who had suffered with irritable bowel syndrome for more than 10 years. For a few weeks prior to that call her symptoms had been unusually severe. She was under another doctor’s care but called me that evening for reassurance and advice.

“At some point, you should consider having a colonoscopy,” I said, a little concerned that an underlying inflammatory bowel disease may be present. Two weeks later …… another call. “I have colon cancer,” she sobbed. Stunned by this revelation I went quickly into “fix it” mode. “I will find you a surgeon,” I replied. She cried. Just like that …. I had left her stranded, abandoned. You see, sometimes in medicine we are cursed when what we know interferes with what the patient needs. At that moment, she did not need a surgeon. She needed much more than that. This was not a 30-year-old white female as noted in the chart. It was Rachel. A wife, a mother, someone's child, sister and best friend.

|

|---|

A few days later the pathology report confirmed an aggressive, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with six of 16 positive nodes. For the next two weeks I sat alone on my porch after work. Each night, as tears streamed down my face, I wrestled. My opponents were “Why her” and “What if” and “Why didn’t I do something sooner?” I reflected on how meaningless the statistics were. Her chance of survival was not 40 percent, as written in the literature. It was 0 or 100 percent. She would live or she would die.

I tried to imagine what this would mean to her at age 30. The hopes and dreams that she may never experience. What about the husband who adored her, or her two little girls? Why should they be asked to carry this yoke? It wasn’t fair. Someone this young should not be standing so close to the finish line. My concentration the next several weeks was hijacked by the image of those two little girls huddled in the bed with their father at night, out of fear that he may be taken away like Mom was. The practice of medicine is a lifelong test for us that reveals our character, while developing it at the same time.

This story has a happy ending. Seven years later, my daughter-in-law Rachel is cancer-free. She and my son now have three beautiful daughters.

This white coat will teach you much more than any lab, small group, clerkship or faculty member. Its lectures are felt, not heard; its lessons so difficult that we all must remediate from time to time. Put on your white coat with humility, for to wear it is an honor.

This white coat.

The witness it will bear.

The stories it will share.

Its pockets filled with important things

Like Barney stickers and plastic rings

A healing cloth, a caring touch

A refuge place within our clutch

This white coat

Hears the mystery of a newborn’s cry

Sees the wonder in her mother’s eyes

Washed with laughter, stained by tears

A cloak of kindness when illness nears

Though worn by those with human hands

Still a symbol of hope for fellow man.

Congratulations, Class of 2015, and welcome to the most blessed of professions.