Pensacola - Kim Landry

From the College of Medicine's 2018 annual report. Part of the 'After the hurricane: Responsive to community needs' series.

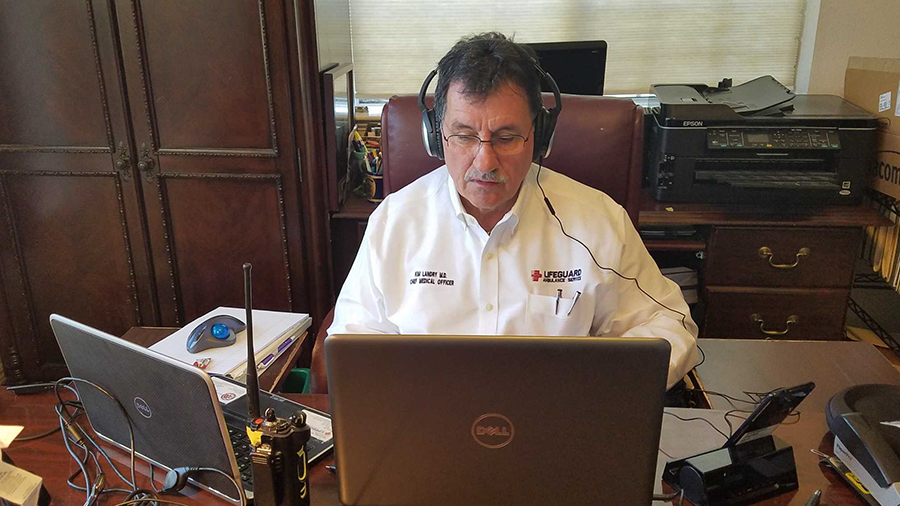

KIM LANDRY, LIFEGUARD AMBULANCE, GULF BREEZE

Chief Medical Officer Landry (M.D., Program in Medical Sciences ’86) saw Panama City patients after Hurricane Michael even though he was more than 100 miles away in Pensacola. The storm presented the perfect opportunity to demonstrate the strengths of telemedicine. (Mark Stavros, M.D., clerkship director for emergency medicine at the Pensacola Regional Campus, was also involved in this project.)

It was the first time we had employed telemedicine during a natural disaster, when local medical resources were profoundly affected or even nonexistent. Telemedicine allowed us emergency physicians at a distant location to be delivered virtually into the disaster region and to begin examining patients with the assistance of paramedics. The digital diagnostic equipment allowed us to perform as close to a face-to-face exam as possible.

In this limited exercise, we evaluated and treated over a dozen patients. Some had lost most of their personal belongings, including prescription medications, and had no way to contact their physician for follow-up visits or new prescriptions. In addition, post-disaster cleanup operations yielded many minor traumatic injuries such as puncture wounds and cuts. Some of these can be treated via telemedicine. Even if they can’t, having an emergency physician using telemedicine to evaluate the patient in the field can really help decompress an overcrowded emergency department. I saw a few traumatic injuries, including an amputated finger, that required treatment at the hospital. A couple of patients were stressed out, causing them to be hypertensive, tachycardic (rapid heart rate) and short of breath. They were evaluated and did not require transport to the hospital.

It worked well, despite only sporadic cellphone and Wi-Fi availability. Fortunately, the system I use (MaxLife Advanced Telemedical Systems) searches for and automatically connects to the strongest cellular signal available, allowing uninterrupted connection between physician and paramedic/patient. Satellite would resolve many connectivity issues, but it costs more.

The paramedics I use are already trained in patient assessment and management of emergency conditions, so I only had to train them on the use of the peripheral equipment (exam camera(s), otoscope, stethoscope, etc.) and how to operate the software installed in the telemedicine cases.

Besides the connectivity issues mentioned above, there are other downsides:

- Prohibitive startup costs. The mobile telemedicine case and all the peripherals run about $31,000 to more than $35,000 each. The cardiac monitor is part of the EMS equipment; however, if a non-EMS telemedical service were to purchase one, it would run another $35,000. On the physician (or hospital) side, it’s a matter of installing the software that connects to the case and having a good set of headphones to listen to heart and lung sounds.

- Lack of reimbursement, even though telemedicine has the potential to save insurance companies and third-party payers a significant amount of money. At least 32 states require insurance companies to reimburse for telemedical services at the same rate as a face-to-face visit. But in Florida, insurance lobbyists have managed to remove any such language from telemedicine bills that have made it through the Legislature.

Telemedicine has tremendous potential for conveniently connecting patients and physicians in both rural and disaster settings who may otherwise go without care. It offers early evaluation and intervention. A patient who may avoid travel to a physician’s office might welcome a virtual physician visit before a relatively minor problem becomes more serious and more expensive.